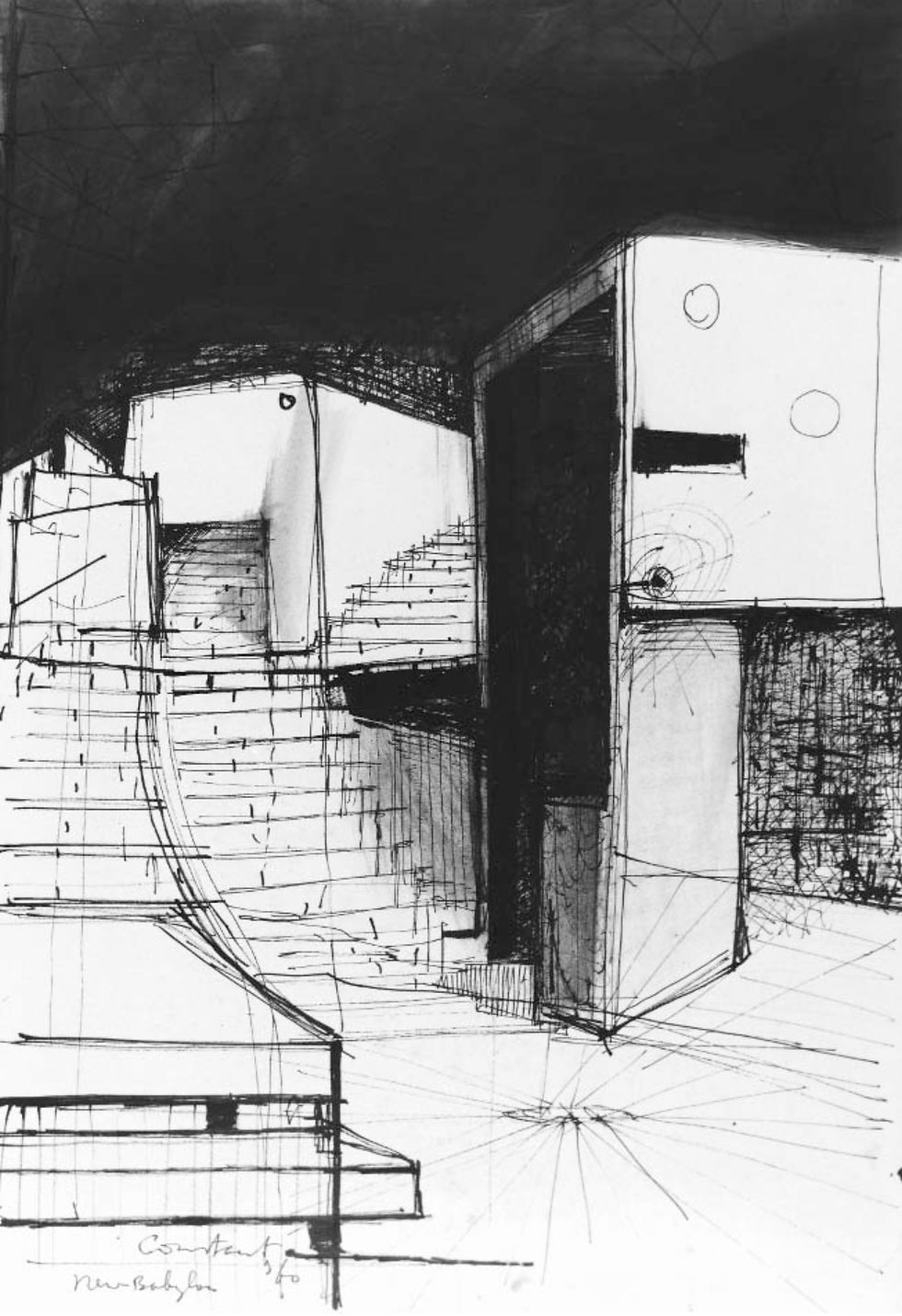

New Babylon was a project conceived by Constant Nieuwenhuys roughly around the dates 1959-1974 (Lefebvre and Ross, 1997), more intensely after parting ways with the Situationists in 1960. It was an attempt at developing the ideas of unitary urbanism further, and to give it concrete form. In the words of Constant himself: “...where, under one roof, with the aid of moveable elements, a shared residence is built; a temporary, constantly remodeled living area; a camp for nomads on a planetary scale.” (Nieuwenhuys, 1974). The theory of Constant was a society which was free of production duties due to automatisation, and has infinite free time. The people, who are called homo ludens (man the player) (Nieuwenhuys, 1974), have total control over the space they are in, which enables them to rebuild the structures as they wish at any given time, creating a city of constant flux. “Nobody therefore will ever be able to return to a place that he visited previously, nobody will ever recognise an image that exists in his memory. This means that nobody will ever lapse into fixed habits.” (Nieuwenhuys, 1974, cited in Heynen, 1999, p. 159). The city will be a collection of ‘sectors’, which is similar to the ‘quarters’ in the Situationist unitary urbanism. As technology and means of production evolve, there will be no need for mankind to work in order to produce commodities. It will all be done automatically, so people, the ‘masses’, will become homo ludens; free to play, explore, experiment, do with their time whatever they please. Heynen says that this can only occur when there is equality of power, no hierarchy in society, and points out the capitalism denouncing quality of this theory. New Babylon is the foreshadowing of this physical environment, to which collective, open spaces are crucial, where a new form of human could thrive in (1999, p. 160).

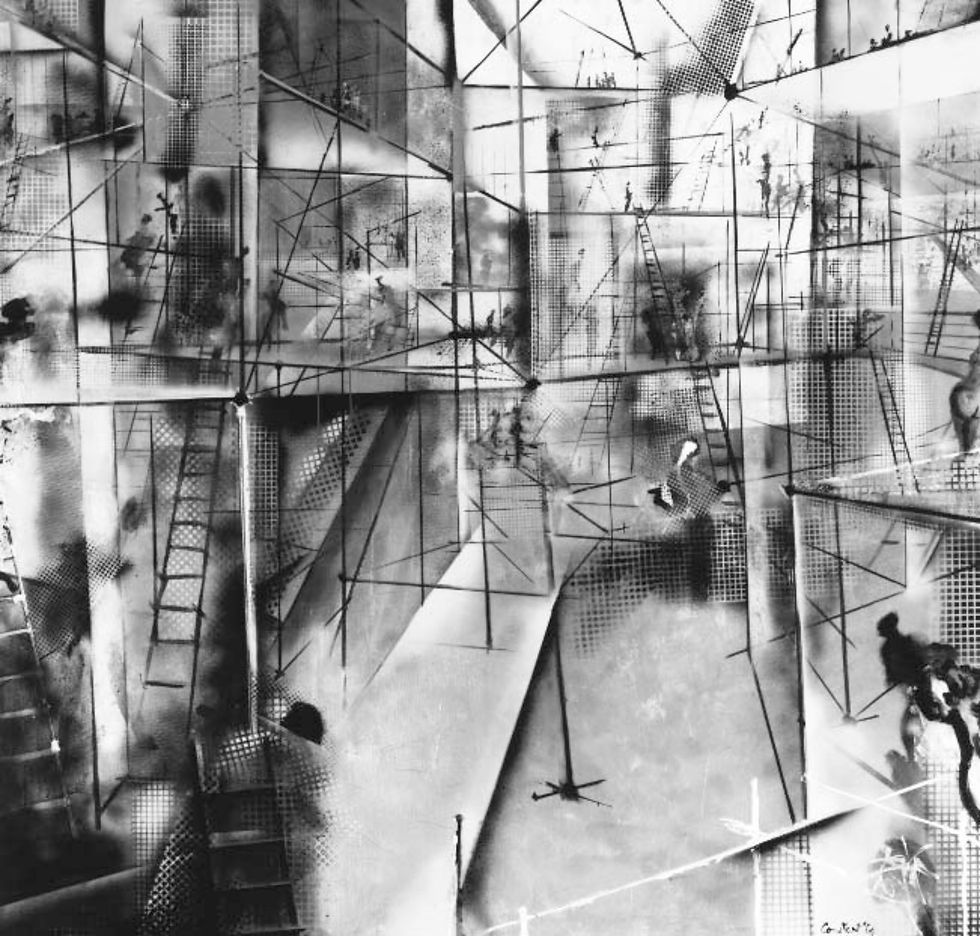

From this point on, Heynen starts to construct her argument about New Babylon. She identifies the inconsistencies between different models, and how the whole concept is not fully developed. She points out Constant’s ‘way out’ of this, by him saying “the real designers of New Babylon will be the Babylonians themselves” (Nieuwenhuys, 1974, cited in Heynen, 1999, p. 164), and mentions that one cannot see this happening in any of the representations, especially the maquettes, and reasons that this was why Constant chose to continue working on New Babylon in drawings and paintings. This part of the chapter is the crucial point where the reader is shown that the ultimate utopia that is New Babylon starts to crumble. Heynen builds up to this with explaining in detail what Constant wanted to convey in his representations, then how he fails to do it, either knowingly or unknowingly. She mentions the feeling of tension emanating visually, giving examples of visual qualities that carry this feeling which is not ideal. She also mentions the ‘feeling of unease’ in New Babylon (fig. 2) (Heynen, 1999, p.169).

The sense of ambiguity and aimlessness that Heynen points out with the rest of the negatively associated qualities of New Babylon, leads to ‘the tragedy of utopia’ (1999, p.172), where she clearly lays down how New Babylon is a failed attempt at presenting a utopia, consciously or unconsciously. This sub-part of the chapter is where she stipulates her critique of New Babylon. She mentions that the conception of Constant lacks the quality of dwelling (1999, p.172), which is a concept remarked upon throughout her book. The inadequacy of the theory was evident to Lefebvre as well. When he was asked how the situations progressed into concrete construction, Lefebvre replied: “Because the architecture of the situation is a Utopian architecture that supposes a new society... well, ‘new situations’ was never very clear.” (Ross and Lefebvre, 1997, p.73).

Constant’s depiction of singular silhouettes (fig. 3) that seem to ignore each other (or maybe are not able to interact with one another) may be related to his representation of autonomy. It may seem relevant, but the concept of New Babylon is built upon unitary urbanism, where everything happens collectively, so this quality of homo ludens in Constant’s work is contradictory. He has a somewhat clear vision of this post revolutionary world, and surely he sees the contradictions that exist in that reality. It may be that working extensively on New Babylon made him realise that no matter how effective a revolution happens, due to the characteristics of human nature, his utopia may never be valid. Heynen makes this case, saying:

“This faith in the revolution and in the human race’s real potential for change is characteristic of the intellectual climate of the sixties in which New Babylon is rooted, but it does not take into account what has in the meantime became known, in Foucault’s phrase, as the ‘micrology of power.’ It ignores the finely meshed interplay between the principles on which the social system is founded and the psychological mechanisms that guide individual behaviour ... The human condition is probably a bit more complicated than that.” (1999, p. 174)

Constant’s New Babylon is aiming to be a utopian city, also conceived as a critique of modernity. Although the main intention was for the users to attribute characteristics to a number of spaces to create a utopia of infinite freedom and leisure, the unlimited emptiness and uniformity instead pushes the user towards loneliness, confusion and disorientation, thus turning it into a dystopia. In an architectural sense, Constant’s spaces which are designed to be universal, can be said to have a lack of character instead, reminiscent of the critiques of the larger examples of the International Style. It furthers the modernist idea of the International Style, creating the ultimate city of confusion. Heynen also mentions Constant’s most likely final representation of New Babylon, Terrain Vague (Wasteland), which, similar to its name, is a vast emptiness that contains hints of past spaces (1999, 172-173). She comments on Constant’s work, “In this sense New Babylon is a striking proof of the impossibility of giving utopia a concrete form and of making poetry the only moment of reality: one cannot ‘dwell’ in New Babylon” (Heynen, 1999, p.175). In explaining the development of unitary urbanism and New Babylon in the way she does, Heynen culminates at the most captivating point of New Babylon, that it is an impossible utopia. Many people who are drawn to the ideas behind New Babylon must do so because of this quality, that there is dystopia contained in the utopia, failure in the ultimate success, inconsistencies and contradictions in the perfectly conceived collective society. Although people dream of and strive for an ultimate society where everyone is content; due to human nature, social, economical, environmental and technological developments and how humanity directs and handles these, a utopia does not seem to be sustainable, or even achievable, in the near future. Heynen finally returns to apply these realisations about New Babylon to Debord’s thoughts as well, ending the sub-part with the notion of the search for authenticity, and how the chase inevitably develops into a loop.

In order to further understand New Babylon and its theory, one must also get acquainted with Manfredo Tafuri’s (1935-1994) ideas which are presented in his book Architecture and Utopia (Progetto e Utopia, 1973). Heynen points this out earlier in her book, (1999, p.130-136), where she explicitly says she is focusing on the parts regarding utopian thought and musings on the avant-garde, doing so to prepare for chapter four (p. 130). According to Heynen (1999, p. 130), Tafuri essentially argues that one cannot comprehend the evolution of modern architecture without considering the capitalist economic structure, that the whole process takes place in this framework. She goes on to explain Tafuri’s stance; “The avant-garde sees ‘destruction’ and ‘negativity’ as vital moments in capitalist evolution. The fact that they experiment with just these elements, rendering them, as it were, plausible for individual experience also has implications for the dissemination of the process of social modernisation” (Heynen, 1999, p.132). Although the avant-garde movements were set out to change the status quo and have definitive effects on capitalist society, Tafuri concludes that they were not successful in this mission. He says that architecture had the role of “giving concrete form to the rationalisation inherent in it [the course of capitalist evolution]” (Heynen, 1999, p.134). This reference to negativity of the avant-garde is significant in understanding the contradictions within New Babylon, and how it failed to be a utopia. Heynen goes on to explore Adorno’s ideas on negativity further in chapter four, after assessing Adorno’s theories to make sense of the contradictions within New Babylon.

Bibliography:

Debord, G. (1957). Psychogeographic Guide of Paris. Denmark: Permild & Rosengreen. Available at: http://imaginarymuseum.org/LPG/debordpsychogeo.jpg[Accessed: 19 February 2016]

Heynen, H., (1999). ‘Reflections In A Mirror’ and ‘Architecture as Critique of Modernity’, from Heynen, H., (1999). Architecture and Modernity: A Critique.Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p.128-148, p.148-193.

Lefebvre, H and Ross, K., (1997). Lefebvre on the Situationists: An Interview. October,n.79. p. 69-83. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778839. [Accessed: 17 February 2016].

Nieuwenhuys, C. (1974). Exhibition Catalogue. The Hague: Haags Gemeetenmuseum. Available at: http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic709752.files/WEEK%207/CNieuwenhuis_New%20Babylon.pdf. [Accessed: 14 February 2016]

This paper was originally written for the module Critical Methodologies in Architectural History.

Comentarios